Sacred Spaces on the East Side Attest to a Hundred Years of History – by Don Mathis (2019)

“The cornerstone of the East Side” is how African American historian Kenneth Mason describes the black churches of San Antonio.

Several African American church buildings still stand after more than a century of use. The City Council and the Office of Historic Preservation are busy with a new survey and designation initiative that focuses on the historic churches of the East Side. Other studies abound.

As the East Side experienced ‘white flight’ in the late 1800s, and as streetcars became available, more and more people of African ancestry moved into the neighborhood. Because the ‘new’ suburbs, such as Government Hill, Laurel Heights, and Beacon Hill, stipulated sales to whites only, the East Side was the only place for blacks to go.

In his book, African Americans and Race Relations in San Antonio, Texas, 1867-1937, Mason mentions how one housing development advertised: “No lots can be purchased at any price for Negroes or other undesirable elements.” Mexican Americans, Chinese, and poor whites were the other ‘undesirable elements.’

“African American churches,” Mason writes, “were erected in political wards that contained the heaviest concentration of blacks.”

Mason identified the most prominent churches were the Colored Methodist Episcopal (established as early as 1866), the African Methodist Episcopal (in 1867), and the First Baptist (in 1871).

“Between 1875 and 1880, the demographic trend toward residential segregation on the near East Side stimulated a proliferation of church building in that part of the city,” he wrote. “It was because so many Baptist churches were established in the Fourth Ward that the area was dubbed the ‘Baptist Settlement.’”

The ‘Baptist Settlement’ included the Free Missionary Baptist, the New Light Free Mission Baptist, and Mount Zion First Baptist. But other denominations proliferated as well.

A year before the Emancipation Proclamation in 1865, the Methodist Episcopal Church authorized the formation of black congregations independent of white supervision. After the Civil War, separate African American churches began to multiply from Mississippi to Texas.

By 1866, the Saint Paul United Methodist Church convened in San Antonio. Their limestone building (built at 230 N. Center in 1884) received a plaque in 2015 from the Office of Historic Preservation designating their original spire as a historical landmark. The St. Paul church building at North Mesquite and Center Street, completed in 1922, is home to several hundred members today.

The New Light Baptist Church organized in 1870. Their sanctuary and educational buildings at 607 Piedmont Ave. were rebuilt in 1941. K. D. Beckmann, an architect who designed many churches and synagogues, built the neo-classical red brick edifice.

Former slaves founded the congregation of Mount Zion First Baptist Church in 1871 but a succession of storms and fires plagued their building on Santos Street. The church moved to its present site (at the corner of Martin Luther King Blvd. and Hackberry) in 1927.Mount Zion has long been a leader in the Civil Rights Movement. The Rev. Claude Black Jr. was a contemporary of Thurgood Marshall, Barbara Jordan, and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and invited many such leaders to speak after he became pastor in 1949. Arson destroyed the church building during Black’s term on City Council (1973-1978) but the community rallied and built a new house of worship in 1975.

A dozen men, linked by their shared experiences as slaves, organized the Second Baptist Church in 1879. In 1894, they moved to Chestnut Street and by 1910 completed a Gothic sanctuary. They moved to their current location at 3310 E. Commerce Street in 1968. The church has played an integral role in the San Antonio for 138 years.

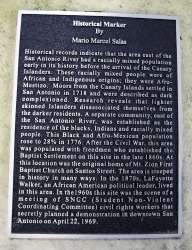

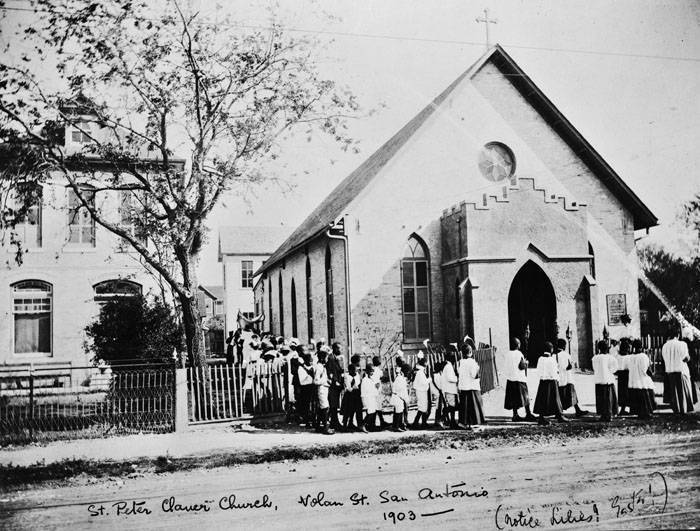

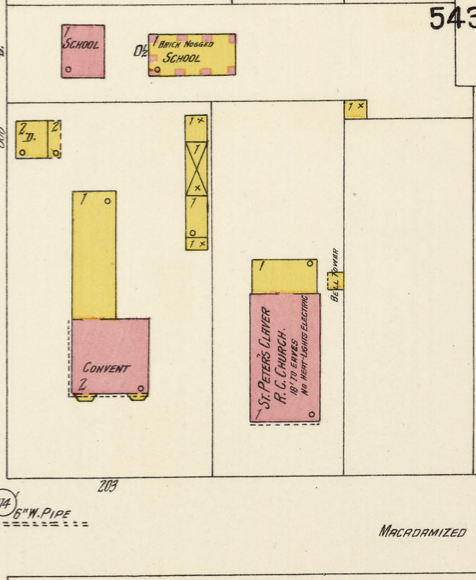

Saint Peter Claver Catholic Church began in 1888 but its history goes back much further. Margaret Mary Healy Murphy performed decades of good deeds before being inspired by a sermon to build a school for African Americans. San Antonio at the time had a reputation for aggressively opposing schools for black children and the Catholic church often neglected its black parishioners.

Named for Saint Peter Claver, the Jesuit priest who had spent his life helping slaves in Spain and Portugal, Murphy’s Colored Mission was the city’s first free school for blacks. Murphy’s finished campus, entirely financed by her estate, included a house of worship with 500 seats, a rectory, and a school for 120 students.The institution founded and funded by Murphy continues to flourish today as the Healy-Murphy Center providing an individualized high school program for students at risk.

In 2016, City Council District Two and the Office of Historic Preservation undertook a survey and designation effort focusing on sacred spaces on the East Side. More than 40 sites have been documented and researched using the Discovery App. Learn more by visiting their inventory map at https://app.localdata.com/#embed/surveys/eastside-churches

XXX

Don Mathis

Don Mathis bio: Don’s life revolves around the many poetry circles in San Antonio. His poems have been published in many anthologies and periodicals and broadcasted on local TV and national radio. In addition to poetry, he has also written policy and procedures for industry, case histories for psychological firms, and news and reviews for various media.