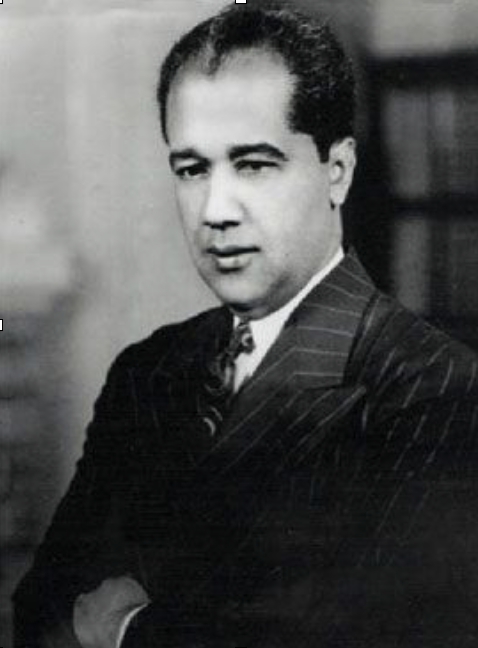

Thurgood Marshall, 1936, Photo Credit: Library of Congress

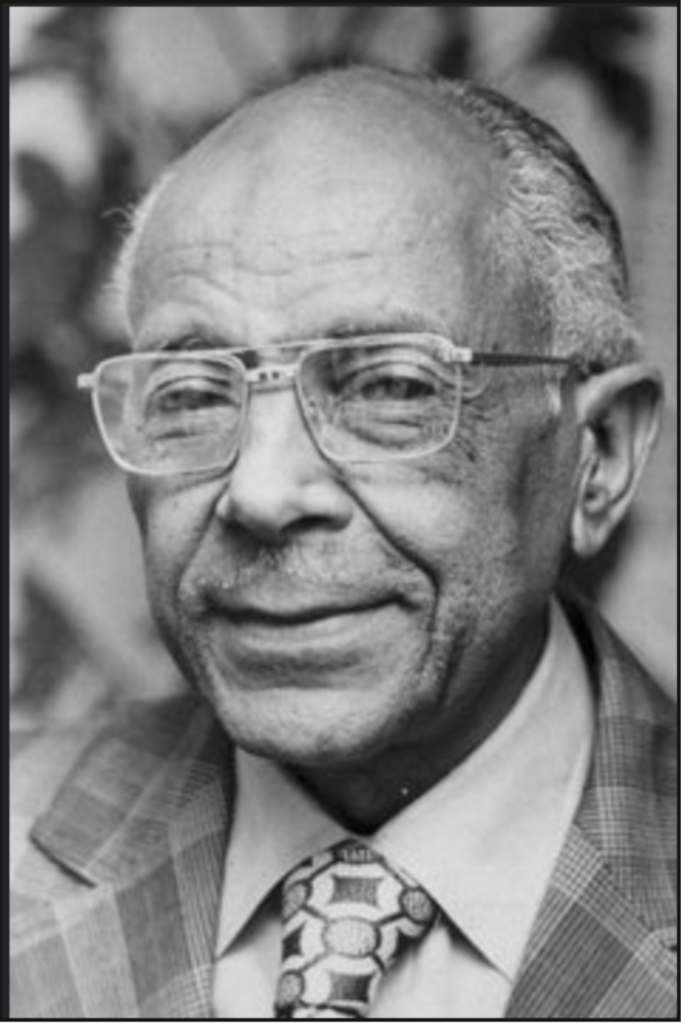

Dr. Lonnie E. Smith, Harris County

In 1944, the Texas Democratic Party’s “white primary” was argued in front of the United States Supreme Court by Thurgood Marshall, in the case Smith vs. Allwright. Houston dentist, Dr. Lonnie Smith sued Harris County election official, S.S. Allwright for the right to vote in a Democratic primary election.The case argued the “white primaries” violated the 14th and 15th amendment. The case overruled the decision of Grovey vs. Townsend that declared the “white primaries” legal.

Some consider this important decision as the birth of the civil rights movement. Thurgood Marshall characterized the ruling of Smith, his most important case and “so clear and free of ambiguity” that the right of Blacks to participate in primaries was established once and for all and a giant milestone in the progress of Negro Americans toward full citizenship.”

In 1940, approximately 200,000 voters were registered in Texas. After the Smith vs. Allwright decision, the number of Southern blacks registered to vote rose to between 700,000 and 800,000 by 1948 and then to one million by 1952.

According to Donald S. Strong’s, the Rise of Negro Voting in Texas”, he questioned Black leaders and White informants across Texas in 1947 about violence at the polls. Strong states his interviews revealed restraints hidden in legalities. For instance in Marshall, Texas the National Guard were stationed at each voting booth to exclude Blacks from voting.

The Black leaders in Marshall requested the guardsmen sign affidavits with the intent to start legal proceedings. The guardsmen withdrew from the polls.

In Colorado County, voters were presented with two ballots, one for state offices and one for county offices. White voters received both ballots but Black voters only received the state-wide ballot. Presumably to keep the Blacks from having power within the county.

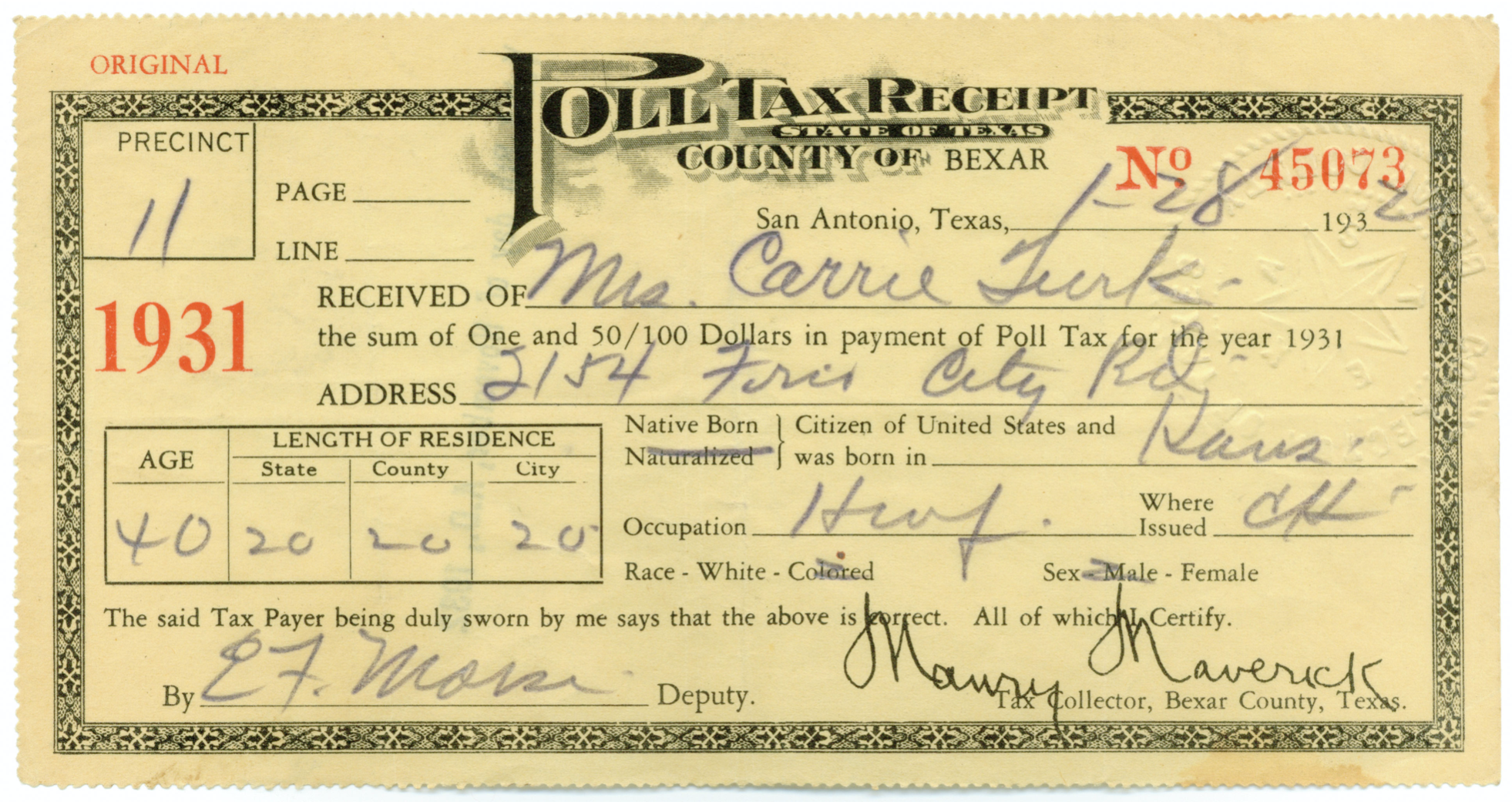

Across the state, pay-your-poll-tax campaigns were organized by churches, the NAACP and schools. In Waxahachie, the campaigns to ensure Black voters paid their poll tax resulted in more Blacks than Whites being able to vote in the 1947 city election. Unfortunately, this instance resulted in city officials not allowing the Blacks to vote. Because this act was unprecedented, the Black voters were caught off guard and did not have a prepared legal remedy.

Other successful voting practices for Blacks were candidate endorsement and block-voting. Candidate endorsement is when a group of community leaders would review the slate of officers. Candidates records were reviewed and discussed among the leaders. The Texas primary ballots in some areas had over 35 offices listed. It was illegal to have aids such as a marked sample ballot to assist your recall. Because of that fact, most groups/leaders did not endorse more than six candidates. Typical endorsements included, governor, US senator, sheriff, district attorney and school board.

Valmo Bellinger

In San Antonio, Valmo Bellinger continued the tradition of his father Charles Bellinger, where most Black voters followed his leadership so the candidate endorsement process was straight forward. Bellinger had a keen interest in the local gambling industry and his political involvement helped to protect his income stream. In 1946, San Antonio was the most machine-controlled city in Texas and Bellinger supported the machine.

Understanding that the machines’s real strength came from the Hispanic vote which outnumbered the Black vote 5 to 1, alliances were crucial to political success.

Bellinger paid Black leaders in each neighborhood to “talk up” a candidate in the weeks leading up to the election. He also paid them to ensure Black voters came to the polls. Although, there was less emphasis placed on improving the living conditions of San Antonio Blacks as compared to other Texas urban areas, the Carver Branch of the San Antonio Public Library and auditorium were built for Blacks to use and the sheriff’s office had a reputation for avoiding brutality among Blacks.

In April of 1947, machine candidate Maury Maverick’s run for mayor was opposed by Bellinger however, the Progressive Voters League, endorsed Maverick. In 1948, an alliance set an unprecedented chain of events in the San Antonio School Board elections. A leader in the Progressive Voters League was elected to the San Antonio Union Junior College District board. Although the junior college had both White and Black branches, it had a single governing board which was all white, prior to the election of the successful candidate G. J. Sutton. The election of Sutton was because of the alliance with San Antonio Hispanic voters. Black and Hispanic voters agreed to support each others candidate. Gus C. Garcia, a young Hispanic lawyer was seeking a trustee seat on the San Antonio Independent School District board. Garcia galvanized the Hispanic voters to vote for him and Sutton. Sutton encouraged the Black voters to vote for him and Garcia. Both elections were won by a small margin. Sutton won by 27 votes.

G. J. Sutton, Photo credit: Internet

Gus C. Garcia, Photo Credit: Internet

By 1948 even with the “white primaries” Black voters were voting “solidly” Democratic. Strong reports the Republicans had not made a gesture to attract the Black vote since 1920 and Blacks were not included on the state Republican committees. Strong also states that the 1946 Democratic primary had a preference for liberal candidates who attract Black voters. Unsuccessful gubernatorial candidate Homer P. Rainey is credited with carrying 85 percent of the Black vote. District Judge Sarah Hughes ran for US Congress in the 5th district. Although unsuccessful she received her most support from the Black wards in Texas.

Content provided by NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the The American Political Science Review, “The Rise of Negro Voting in Texas”, Donald S. Strong, University of Alabama

For more history of African Americans and voting in Texas, see our digital exhibit opening, October 13.