Life Before Death: African American Travel Guides and Funeral Homes

by James C. Thomas

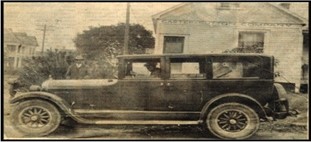

The Tuesday morning August 15, 1911 edition of the San Antonio Express carried a front-page article of the trial of William McWilliams. McWilliams, a white 70-year-old man, was being charged with the murders of a mixed family by the name of Casaway. He was suspected of killing Alfred Louis a Black man, his wife Elizabeth a white woman, and their three children at 417 North Olive Street. The court called in J.W. Williamson, a Black undertaker and funeral home owner, to testify about what he saw when he went to recover the mutilated bodies from the scene.[1] Undertakers at times played an important part in the justice system, and at times found themselves in it. October 14, 1937 issue of the San Antonio Express wrote an article about Cy Garner, a Black man, from Collins Undertaking who “was accused of exhibiting a pistol and threatening the life of Jeff Conaway, a Negro, 601 North Center Street, driver for the Carter Undertaking Company.” They were fighting over who would claim the body of murdered Henry Thomas for their respective funeral homes.[2] There were a number of Black owned funeral homes in San Antonio at the time and a competitive nature among the businesses. This aggressive nature could also be seen when funeral directors were fighting for civil rights. Bill Vollmer wrote an article in June of 1963 about funeral director and San Antonio NAACP chairman J.E. Taylor. The article was about Taylor organizing and getting the proper permit to have a march “for slain Mississippi civil rights leader Medgar W. Evers.” He wanted to assure the public that his planning of this march and his work with the desegregation committee of San Antonio was of “no relation.”[3]

Publications like the Green Book, Grayson’s Travel and Business Guide, and Chauffer’s Travel Bureau Guide were essential to African American travel in the United States during the Jim Crow era. These travel guides were a proverbial “drinking gourd” for African Americans to find safe havens in a segregated and often violent south. The guides listed gas stations, hotels, and even night clubs for most of the continental United States’ major cities. Such establishments are usually the first places that people think about when discussing travel during the era as the primary focus of the guides was to get African Americans safely from “point a” to “point b” with dignity and enjoyment. Ironically, businesses that dealt with the dead had a reputation for assisting Black Americans through the fullness and possibilities of life. While most travelers hoped they would not need the morbidity of an undertaker on vacation, the contact information could come in handy for other reasons. Funeral home owners, because of their economic independence and leadership, were often some of the most influential Black leaders in a given town. Creators of the travel guides knew this and made sure to include funeral homes so that travelers knew they were part of the conversation, influence, and life of a town.

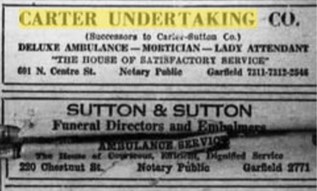

Carter Undertaking Company, listed in the 1949 editions of Grayson’s Travel and Business Guide at 601 Center Street in San Antonio, Texas, is one such example of the vibrancy and influence that stretch out from homes for the dead. Using the Carter Undertaking Company as the representation of African American funeral homes around the country, the focus of this paper will be on the funeral experience provided to the families, the entrepreneurship and business partnering of Blacks to provide a service and create personal financial independence, and the civil rights work Black funeral directors undertook to fight for the rights of African Americans during the era of the Negro Travel guides. In conjunction with the history of Carter Undertaking all of these aspects will be covered.

Funeral homes and undertakers were one of the first businesses that African Americans invested, as funerary services like most industries were segregated. Business ownership created the ability to become financially independent without the aid of white patronage. Never lacking customers within their exclusively Black clientele, the capital made by funeral directors afforded them the freedom to speak out on situations that plague the African American community.

In 1906 in the city of San Antonio, Texas, J.W. Williamson and his son George founded the Williamson and Son Funeral home, it was the first African American undertaking business in the city. [4],[5] Across the south and cities with large African American populations saw the opening undertaking businesses that exclusively served the community, as there was a market for it. This rise in ownership was largely due to Jim Crow discrimination. Some white funeral homes often refused to deal with the Black deceased. Those that did and had the financial capabilities to do so built a separate wing onto their pre-existing establishments to maintain racial separation. [6] White funeral home owners and whites within the growing industry of the early to mid-20th century tried to keep the Black patrons away from the Black funeral directors. White business owners tried to keep trade secrets and the “largest opportunities in the field were reserved for ‘Whites only’ ”.[7] In newspapers like the San Antonio Express during the 1940s, Black funeral homes were classified in the business and professional directory as “colored.” The fact that this description was placed in the newspaper gives way to understanding that racial segregation was important in the south and even prevalent in San Antonio.[8] Still, some African American families continued to patronize white undertakers (they believed that white undertakers were better), though the deceased family members were not always treated with dignity and respect.[9] Still, many African Americans chose Black undertakers not just for the care that they provided but for the rituals, beliefs, and religious aspects that were indicative of Black culture. The burial practices or “homegoing” that African American undertakers provided were rooted in African traditions, rituals, and beliefs passed down through slavery. From the way the bodies were prepared to the singing of Negro spirituals, the Black undertaker facilitated the funeral in a way that honored the dead’s African and Christian beliefs.[10] In 1921 ownership of the funeral home changed hands and was sold to Oliver Jackson (O.J.) Carter with business partner Samuel Johnson (S. J.) Sutton, and became known as the Carter-Sutton Funeral Directors.[11] Even under new directors the burial and funeral practices that they learned from the Williamsons with its traditions set in African and Christian beliefs, aided in their business becoming one of the most successful Black owned funeral homes and businesses in the city.

African American undertakers and funeral homes’ service to the community cannot be understated. Dignity, respect, and a proper burial were important in the Black community, but these businesses also served another purpose as they created an untouchable Black entrepreneurial class. The expansion of Black owned businesses, in particular, funeral homes was not lost on San Antonio. While Carter-Sutton funeral directors were doing well other Black funeral home owners, like Frank E. Lewis, who founded his establishment in 1909, were also thriving.[12] Across the country, more and more African American funeral homes were being established. Though the industry was segregated initially, white owned funeral parlors refused to deal with deceased African Americans. Over time, a tradition evolved as did the overall idea that Black customers would patronize Black establishments when available, especially funeral homes.

Despite their prominence even Black funeral directors were excluded from the National Funeral Directors Association. So, they established their own.[13] Originally called the Independent National Funeral Directors Association (INFDA) they “sought to support research, develop standards for the profession, and encourage African American participation in the mortuary field.” The association started in larger cities but as the profession flourished among African Americans, they found members in smaller and more rural areas of the country. They eventually began to publish literature like, The Colored Embalmer, which later became known as, The National Scope; this expansion on a national level helped many local establishments grow as they shared trade secrets and ways to modernize their operations. [14],[15] With this expansion of Black owned funeral homes, it created something that few Blacks hadn’t experienced in America to this point—financial independence.

Illustration of O.J. Carter from the San Antonio Light newspaper June 20,1901 [16]

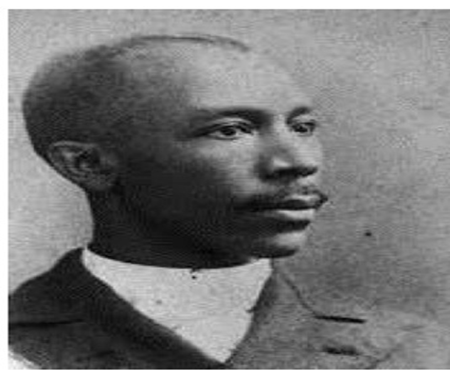

Photo of Samuel Johnson Sutton [17]

The undertaking business created an entrepreneurial spirit and financial independence for Blacks during a time when it was almost impossible to do so. One of the richest and most well known Black undertakers was James C. Thomas of Galveston, Texas. He started his highly successful undertaking business in 1897 in New York City. Thomas expanded his horizons, flipping the initial capital from the undertaking business into other entrepreneurial endeavors like real estate. By the time of his death in 1922 his holdings were at $500,000.[18] Adjusted for inflation, $500,000 in 1922 is equal to $ 8,556,666.67 in 2022.[19] According to Booker T. Washington businessmen like James C. Thomas bolstered Black business. Black craftsmen and skilled workers who opened their own shops, patronizing Black customers, and keeping the Black dollar in what W.E.B. Du Bois called a “group economy.”[20]

With the passing of O.J. Carter in 1927 his widow Annie Edith Carter and Sutton continued running the business as partners. In 1936 S.J. Sutton left the partnership of Carter Sutton Funeral Directors to establish his own funeral home business. Indeed this was the outcome of many partnerships. Intrigued by financial independence, partners split to start their own funeral home business as well as embark on other projects. [21] Sutton used his finances and his knowledge of business to open up other establishments like a “skating rink,…mattress company, and a farm.”[22]

Photo of James C. Thomas, circa 1903 [23]

Carter-Sutton Company Funeral Home with Jeff Conaway (in car) and Harold Ryce (behind car), c.1930 [24]

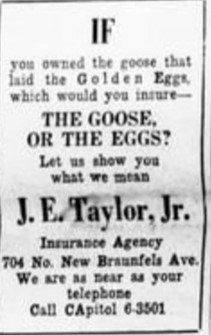

After the departure of Sutton, the funeral home would go through yet another name change, this time to Carter Undertaking. While under the direction of Mrs. Carter the business did a lot more advertising in local newspapers and magazines. She carried on the continued success of the business until age and health became an issue. Mrs. Carter brought in her niece and her husband Mr. and Mrs. James E. Taylor to run the business.[25] J.E. Taylor was familiar with running a successful establishment as he had already been running a notable “life insurance and a real estate agency.”[26] As a licensed CAA pilot he also ran a flight school as an instructor.[27] The wealth that funeral directors earned made them important people in the Black community. While many of them were already active in the community their wealth and influence aided in them being leaders in the efforts for civil rights.

Advertisement in the San Antonio Register for Carter Undertaking Company in 1937. Underneath is an ad for Sutton and Sutton Funeral directors. This is roughly within a year after S.J. Sutton left the partnership. [28]

Advertisement for J.E. Taylor’s Insurance Agency in the San Antonio Register circa 1959. [29]

The wealth that funeral directors accumulated made them important figures in the community. They were known by the masses for the ubiquitous services they provided and in turn were well connected. They were leaders within the Black community and their financial independence and notoriety gave them a platform on which to speak. Many funeral directors were active in various community, city, and state projects along with the civil rights movement through well known organizations. In the south some funeral directors were highly involved with organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the NAACP. They would often put aspects of their business on the line in the cause for freedom, be it with their “professional, financial, and political aid.”[30] Notable activist organizations would often turn to respected and financially independent funeral directors with help “for bail money, to negotiate compromises with local white leaders, or-in the worst cases-to prepare the bodies of slain civil rights workers for burial.” [31]

This level of involvement was customary and expected from the line of funeral directors at Carter Undertaking. Before becoming a funeral director O.J. Carter was involved in the Black community of San Antonio. He served as the secretary on the Riverside Park Emancipation celebration committee that organized festivities for a Juneteenth celebration in 1897.[32] As the church clerk for Second Baptist Church under I.H. Kelley as pastor, he wrote a letter to the mayor of San Antonio with a small donation in aid to the city of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake.[33] Carter also worked as the secretary for the Y.M.C.A. in 1919.[34] He was one of the first Blacks to serve on the grand jury in Bexar County, but his contributions would not be outdone by his wife.[35] Annie Edith Carter worked in the community mainly assisting Black orphans. While working with the Woman’s Progressive club and Artemesia Bowden of St. Phillip’s Normal and Industrial school, Annie Carter assisted by raising money, food, fuel, clothing, and a fundraiser for a new building for the Ella Austin Home for Negro Orphans and Aged.[36] The orphanage was the only one that served Black children and the elderly during the time.[37] In 1955 she was part of a delegation of Black leaders from the East side that went to the city manager to discuss municipal swimming pools being segregated.[38] Mr. and Mrs. Carter’s commitment to the Black community and civil rights was important to the city in the early part of the 20th century.

“Ella Austin Orphanage on Burnet Street (photo from the San Antonio Light Collection)” [39]

The community and civil rights work that S.J. Sutton did before and during his partnership with Carter Sutton Funeral Directors was imperative and impactful to the East side (while his worked continued after he left the partnership this paper will only cover up until he left Carter Sutton Funeral Directors). Sutton worked in education for many years serving the Black community’s youth. He was the principal of Douglass High school and Wheatley High school, both colored schools.[40] Sutton was also the president of the local Volunteer Health League. He helped to organize “Negro Health Week” in San Antonio which was a state wide program to teach health and hygiene practices to Blacks.[41] Sutton was involved in almost every aspect of the Black community, and continued his work progressing Black lives in San Antonio after departing from Carter-Sutton.

James Edward Taylor Jr. was one of the most outspoken civil rights leaders in San Antonio about worker, religious, and civil rights. J.E. Taylor was the local chairman for the NAACP and planned the memorial march for assassinated NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers. In the June 23, 1963 San Antonio Express article Taylor is quoted as saying:

This struggle for universal freedom is not merely an action by and for Negroes. Our activities, as a minority, merely say to those of the majority that ‘you have been tolerating an impossible situation. Among the heroes who fell at the Alamo was a Negro-‘John.’ He was one of the many of our group who have died in defense of the ideas and the ideals of our native land. From Boston Commons to the streets of Jackson, Miss., our minority has shed its blood for a yet elusive freedom.[42]

Though San Antonio’s narratives of Jim Crow were different and perhaps milder than other deep south communities, it didn’t keep Taylor from fighting just as hard for equal rights and equal employment opportunities.[43] He was part of the City Council’s Committee on Desegregation. He fought for not only getting the hotels and restaurants in the city desegregated but the workforce as well.[44] As a devout Catholic, Taylor also brought claims against the Knights of Columbus for not accepting “membership from qualified Catholic Negro.”[45] When he passed in December of 1966, he had been a teacher at Wheatley High School and served on numerous boards including the Boys Clubs of San Antonio, San Antonio Public Library, the Ella Austin Children’s Home, Welcome Home for the Blind, and Bexar and Adjoining Counties Teacher’s Associations.[46] Mr. and Mrs. O.J Carters, Samuel J. Sutton, and James E. Taylor were not just funeral directors but civil leaders in the Black community of San Antonio. They sought out the best for their people in a society that wasn’t the best toward them. While they didn’t always achieve their ideal outcomes, they provided the community the best that they could.

Photo of Mr. and Mrs. J.E. Taylor newspaper interview, circa 1958. [47]

Black funeral homes like Carter Undertakers, were important to the Black San Antonio burial needs, business structure, and community. When segregation tried to reduce African Americans to second class citizenship, African American developed their own institutions to take care of their own. Carter Undertaking provided the needed care for the homegoing of the African American deceased that “served the living” with their “satisfactory service.”[48] They helped to keep what little dollars there was in their sections of the city, while still providing for those in need. Funeral director independence made room for advocacy on the local and national scene and throughout Black civil rights organizations. Having businesses like Carter Undertaking listed in travel guides alerted travelers and locals alike that Black funeral directors were the leaders and spokespersons in the communities. Though many associate them with death and sadness, Black funeral directors served the living by providing hope, faith, and life, for here and after.

Works Cited

[1] San Antonio Express, “With a Smiling Face Defendant Hears Evidence,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), August 15, 1911, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth431463/m1/1/zoom/?resolution=3&lat=4084.2379670448177&lon=698.9024959788077.

[2] San Antonio Express, “Undertakers’ Row Over Body Ends in Court,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), October 14, 1937, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=AAHX&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40AAHX-1616B4C50D209766%402428821-1616736AF01D589F%4017-1616736AF01D589F%40.

[3]Bill Vollmer, “NAACP Slates S.A. Memorial March Sunday,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), June 19, 1963, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-16201812534BF4CE%402438200-161FA7DA6DCCE946%4035-161FA7DA6DCCE946%40.

[4] Carter-Taylor-Williams Mortuary, “Our Story,” www.ctwmortuary.com, https://www.ctwmortuary.com/our-story.

[5] Walk on the River, directed by Born Logic Allah, produced by Baba Aundar Ma’at (2018; San Antonio: Melaneyes Media, 2018), DVD.

[6] “The Need for Black Undertakers,” The Business of Black Death in Detroit (blog), https://tbobdid.wordpress.com/the-need-for-black-undertakers/.

[7] Suzanne E. Smith, To Serve the Living: Funeral Directors and the African American Way of Death (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), Page 45, https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674054646.

[8] San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), April 20, 1941, [Page 60], https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-NB-1611C12AEE98B48A%402430105-16118366FAADAF79%4059-16118366FAADAF79%40.

[9] Donna R. Braden, Black Entrepreneurs during the Jim Crow Era (blog), accessed 2018, https://www.thehenryford.org/explore/blog/black-entrepreneurs-during-the-jim-crow-era/.

[10] Smith, To Serve, Pages 15-32.

[11] Carter-Taylor-Williams Mortuary, “Our Story,” www.ctwmortuary.com.

[12] Lewis Funeral Home, “Our Beginnings,” www.lewisfuneralhome.com, https://www.lewisfuneralhome.com/about-us.

[13]Braden, Black Entrepreneurs during the Jim Crow Era (blog).

[14]Christopher Harter, “National Negro Funeral Directors Association,” amistadresearchcenter.tulane.edu, last modified 2012, http://amistadresearchcenter.tulane.edu/archon/?p=creators/creator&id=854#:~:text=The%20National%20Negro%20Funeral%20Directors%20Association%20began%20in,September%206%2C%201924%20by%20R.R.%20Reed%20of%20Chicago.

[15] Braden, Black Entrepreneurs during the Jim Crow Era (blog).

[16] San Antonio Light, O.J. Carter, June 20, 1901, illustration, https://www.vamonde.com/posts/city-cemetery-3-tour-stops/11169/.

[17] UTSA Digital Collections, Samuel Johnson Sutton, photograph, https://www.tpr.org/podcast/fronteras/2021-02-19/fronteras-san-antonio-museum-educates-and-enlightens-on-local-african-american-history.

[18]Associated Negro Press, “Negro Embalmer Passes Away,” Negro Star (Wichita, KS), June 16, 1922, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&t=&sort=YMD_date%3AA&page=37&fld-base-0=alltext&maxresults=20&val-base-0=%22%20James%20C.%20Thomas%22&docref=image%2Fv2%3A12ACD48DAF81B0D9%40EANX-12C1772D76B5B108%402423222-12C1772D85F2DF78%400&origin=image%2Fv2%3A12ACD48DAF81B0D9%40EANX-12C1772D76B5B108%402423222-12C1772D85F2DF78%400-12C1772DB79D2EC0%40Mortuary%2BNotice.

[19] Study Finance.com, “$500,000 in 1922 is worth $8,556,666.67 today,” Study Finance.com, https://studyfinance.com/inflation/us/1922/500000/.

[20] Smith, To Serve, [Page 44].

[21] Carter-Taylor-Williams Mortuary, “Our Story,” www.ctwmortuary.com.

[22] Brauna Marks, “San Antonio Roots: The Sutton Family & Perry Ellis Sutton,” Spectrumlocalnews.com/, last modified February 28, 2019, https://spectrumlocalnews.com/tx/san-antonio/news/2019/02/28/san-antonio-roots–the-sutton-family—perry-ellis-sutton.

[23] Colored American, “Gotham’s Business Men. Mr. James C. Thomas, the Pioneer Undertaker and Embalmer-Notes in His Career,” Colored American (Washington (DC), District of Columbia), November 21, 1903, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A12B2889871B31178%40EANX-12C5FBCA6502A7B8%402416440-12C5FBCA8219F2D8%406-12C5FBCAE8EECA50%40Gotham%2527s%2BBusiness%2BMen.%2BMr.%2BJames%2BC.%2BThomas%252C%2Bthe%2BPioneer%2BUndertaker%2Band%2BEmbalmer-Notes%2Bin%2BHis%2BCareer.

[24] Charles W. Hunt, Factors that Affect Succession in African-American Family-Owned Business: A Case Study MLA 9th Edition (Modern Language Assoc.) Hunt, Charles W. Factors That Affect Succession in African American Family-Owned Businesses: A Case Study. Universal-Publishers.com, 2012. APA 7th Edition (American Psychological Assoc.) Hunt, C. W. (2012). Factors That Affect Succession in African American Family-owned Businesses: A Case Study. Universal-Publishers.com. (Boca Raton, FL: Dissertation. Com, 2006), Page 44, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=538792.

[25] Carter-Taylor-Williams Mortuary, “Our Story,” www.ctwmortuary.com.

[26] San Antonio Express, “Civic Leader James Taylor Dies at 58,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), December 20, 1966, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-NB-162AC1D415801AA5%402439480-1626D89B28F19B76%4039-1626D89B28F19B76%40.

[27] San Antonio Express, “Thanksgiving,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), November 16, 1958, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-NB-161FA27B04E00468%402436524-161DB845C9A63BBE%4019.

[28]San Antonio Register (San Antonio, TX), September 17, 1937, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth398332/m1/8/zoom/?q=%22Carter%20Undertaking%22&resolution=4&lat=5443.459314463935&lon=1668.5549310405295.

[29] U. J. Andrews, “Advertisement for J.E. Taylor Insurance Agency,” San Antonio Register (San Antonio, TX), May 29, 1959, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth399638.

[30] Smith, To Serve, Page 116.

[31] Smith, To Serve, Page 115.

[32] San Antonio Light, “Additional Attractions,” San Antonio Light (San Antonio, TX), June 17, 1897, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A1432DBB4AA9B7B12%40EANX-NB-171F66420EC51433%402414093-171D1BAF4F03B8E2%403-171D1BAF4F03B8E2%40.

[33] San Antonio Light, “Contributes $12,” San Antonio Light (San Antonio, TX), April 24, 1906, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A1432DBB4AA9B7B12%40EANX-NB-171D255154AD3F92%402417325-171D20F769A71524%402-171D20F769A71524%40.

[34] San Antonio Express, “Y.M.C.A. to Organize Branch for Negroes,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), February 28, 1919, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-15903F6C1F7F30D4%402422018-158EA02D8A8F25D3%403-158EA02D8A8F25D3%40.

[35] San Antonio Express, “Well Known Negro Dies,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), June 25, 1927, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-NB-15D6067A5AFFCC28%402425057-15D56D262431CEAC%4017-15D56D262431CEAC%40.

[36] San Antonio Light, “Minnesotan Has Delusion Dissipated,” San Antonio Light (San Antonio, TX), November 6, 1925, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A1432DBB4AA9B7B12%40EANX-NB-171E33C4870753FC%402424461-171E2956C6237EAD%400-171E2956C6237EAD%40.

San Antonio Light, “Orphanage Asks Food, Fuel Aid,” San Antonio Light (San Antonio, TX), October 14, 1933, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A1432DBB4AA9B7B12%40EANX-NB-171FD5180FD2E93D%402427360-171FCF3B795E9225%4030-171FCF3B795E9225%40.

[37] Isaac L. Godoy, Progressive Era Activism for Black Orphanage, Page 1, 2020, https://saaacam.org/texas-am-san-antonio-student-work-methods-of-historical-research-spring-2020/.

[38] San Antonio Light, “Rice, Negro Leaders Set Talks on Parks, Swimming Pool Segregation,” San Antonio Light (San Antonio, TX), January 17, 1955, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A1432DBB4AA9B7B12%40EANX-NB-17295E2208FB5590%402435125-17295A640963909A%402-17295A640963909A%40.

[39] Ella Austin Community Center, “Ella Austin Orphanage on Burnet Street (photo from the San Antonio Light Collection)”, photograph, https://www.ellaaustin.org/about.

[40] Cary Clack, “Son of Slaves Fathered Highly Accomplished, Inspiring Family,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), May 13, 2017, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-NB-17CD3DA3083BED9C%402457887-17CD3B52695E5841%408-17CD3B52695E5841%40.

[41] San Antonio Express, “Negro Health Week Program Opens Mar.30,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), March 30, 1930, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-NB-15FA62EFC7CDC8A5%402426059-15F65DEFDAA5950B%4017-15F65DEFDAA5950B%40.

[42] San Antonio Express, “Evers Memorial Participation Urged,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), June 23, 1963,https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-1620181EE791C33D%402438204-161FA7DC1A39DC4A%4055-161FA7DC1A39DC4A%40.

[43] Carey H. Latimore, “Civil Rights in San Antonio: WW II to Mid-1960s,” TAMUSA.blackboard.com, https://tamusa.blackboard.com/webapps/blackboard/execute/content/file?cmd=view&content_id=_1986200_1&course_id=_259641_1.

[44] San Antonio Express, “Expanded Integration Proposed,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), July 3, 1963,https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-16201C31CFEFE729%402438214-161FA7C5CB01710B%4037-161FA7C5CB01710B%40.

[45] San Antonio Express, “KofC Head Denies Race Bias Charge,” San Antonio Express (San Antonio, TX), September 28, 1963, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA20F1A545758%40EANX-16203D6F87E53440%402438301-16203C8D7B5B601E%4034-16203C8D7B5B601E%40.

[46] San Antonio Light, “J.E. Taylor Dies in San Antonio,” San Antonio Light (San Antonio, TX), December 20, 1966, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.tamusa.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1432DBB4AA9B7B12%40EANX-173214960F861E91%402439480-17321245985E9D75%404-17321245985E9D75%40.

[47] San Antonio Express, “Thanksgiving.”

[48] Smith, To Serve .

San Antonio Register (San Antonio, TX), September 17, 1937, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth398332/m1/8/zoom/?q=%22Carter%20Undertaking%22&resolution=4&lat=5443.459314463935&lon=1668.5549310405295.